The Post-Modern Virtues of Being an Undecided Major

2002-03

Gene A. Budig Teaching Professor of Education

Thomas S. Krieshok

Lecture delivered October 10, 2003 in Lawrence, Kansas

To be uncertain is uncomfortable, But to be certain is ridiculous. — Chinese Proverb

Let me begin by saying how honored I am to have been named the 2002 Gene A. Budig Teaching Professor of Education.

I am humbled to be able say I hang out with the group of previous awardees, who include Fred Rodriguez, Ray Hiner, Sherry Borgers, Nona Tollefson, Susan Gay, Bob Hohn, and Diane Nielsen. Would those folks mind standing for a moment so we can recognize you and immediately increase my credibility?

Since it was announced last spring that I would be giving this talk, many folks have come up to me reminding me there’s no such thing as a free lunch, implying that this talk is payback for receiving the award. While there have been moments over the past couple of weeks where that has felt true, the story I have chosen to remind myself most often is that this is a terrific opportunity to share with my School of Education colleagues and some of my friends and family just what it is I’ve been up to at work for the past 25 years. My goal for the next 30 to 40 minutes then is to describe some recent developments in the field of vocational psychology, the field to which I am passionately committed.

Let me offer a caveat. For the sake of argument, I am going to take some poetic license and argue for a position that is fairly extreme. I’m not sure even I believe some of the things I’m going to say today.

The Punch Line

The main point that I hope to make is this: For the past 20 years, and maybe for much longer than that, vocational psychology has been selling the wrong product or promoting the wrong outcome, namely the matching of a person to a field of work. And we have done this at the expense of teaching people how to have a healthy relationship to the world of work (a phrase I’ll define in a minute).

Clients, students, and their parents, and even schools and universities, have come to us asking that we help them or their students pick an occupation or a major, or identify the next field for them to pursue. The sum and substance of our work has become the decision, the one that points to that match. Getting decided has become the holy grail of career outcomes. Most people see it something like graduating from high school: You struggle to do it once and then thank God you never have to do it again.

As educators we have colluded with what our students or clients have told us they want, and have made our sincerest efforts at trying to help them find that one thing to which they would be best suited. People who cannot find that match are labeled undecided, and we marshal our resources to move them past that point, sometimes not so gently. In their efforts to improve what they can offer in an increasingly competitive higher education marketplace, some college campuses have reduced the evaluation of career center effectiveness to the popular and easily measured variable of choice of college major. And some colleges even boast that they will only admit students who have committed to a major on their college application. Unfortunately, committing to a college major, especially when not yet ready to do so, may have more negative consequences than simply admitting that one is still undecided.

Let me go back and define the term I left hanging. By “healthy relationship to the world of work,” I am referring to one’s ability to move about in, transition into and out of, and accurately appraise one’s strengths and weaknesses as a player in the world of work.

While we have made strides in our thinking about a person’s relationship to work (e.g., Richardson, 1993), we have not as specifically addressed a person’s relationship to the world of work.

I am not talking about one’s abilities as a worker per se, because someone could be a great worker while remaining naive about their lack of prospects or marketability should their current job be terminated. I am calling this set of abilities the adaptive vocational personality style, and I am going to argue that teaching people how to personify this style should be our new focus, our most desirable outcome for the future.

Three Arguments in Support of a New Focus

I am basing my argument on three main points: First, the matching model has never worked as well as we have wanted it to; second, humans are just not very good at explaining why we like the things we like, a critical element in helping folks find their match; and third, even if there was a time when matching did work, today’s world of work is so turbulent that we can no longer count on keeping our match.

Along the way I will offer qualified support for being an undecided major in college, though as I have already noted, there is no such thing as a free lunch. To qualify for my undecided major status requires a commitment of time and energy that goes well beyond that required of a decided major.

Argument 1: The matching model has never worked as well as we wanted it to.

Vocational psychology traces its roots to Frank Parsons’ work in the Vocational Bureau in Boston in the early 1900s. His book, Choosing a Vocation, published in 1909, laid out a three-pronged approach to guiding people (particularly young people) into the world of work. That model required a) Self-knowledge, b) World of work knowledge, and c) True Reasoning, something akin to common sense when trying to match one’s abilities to opportunities in the world of work.

That Parsonian Triad, as it has been called, formed the basis of vocational psychology’s subsequent trait-factor theories of vocational behavior. In a nutshell, those theories hold that jobs require different aptitudes and personalities, and that the world just happens to deliver workers with different combinations of these same aptitudes and personalities. The trick is to do a good job of assessing those in the person, and then matching them up with what we have learned about occupations in the world of work.

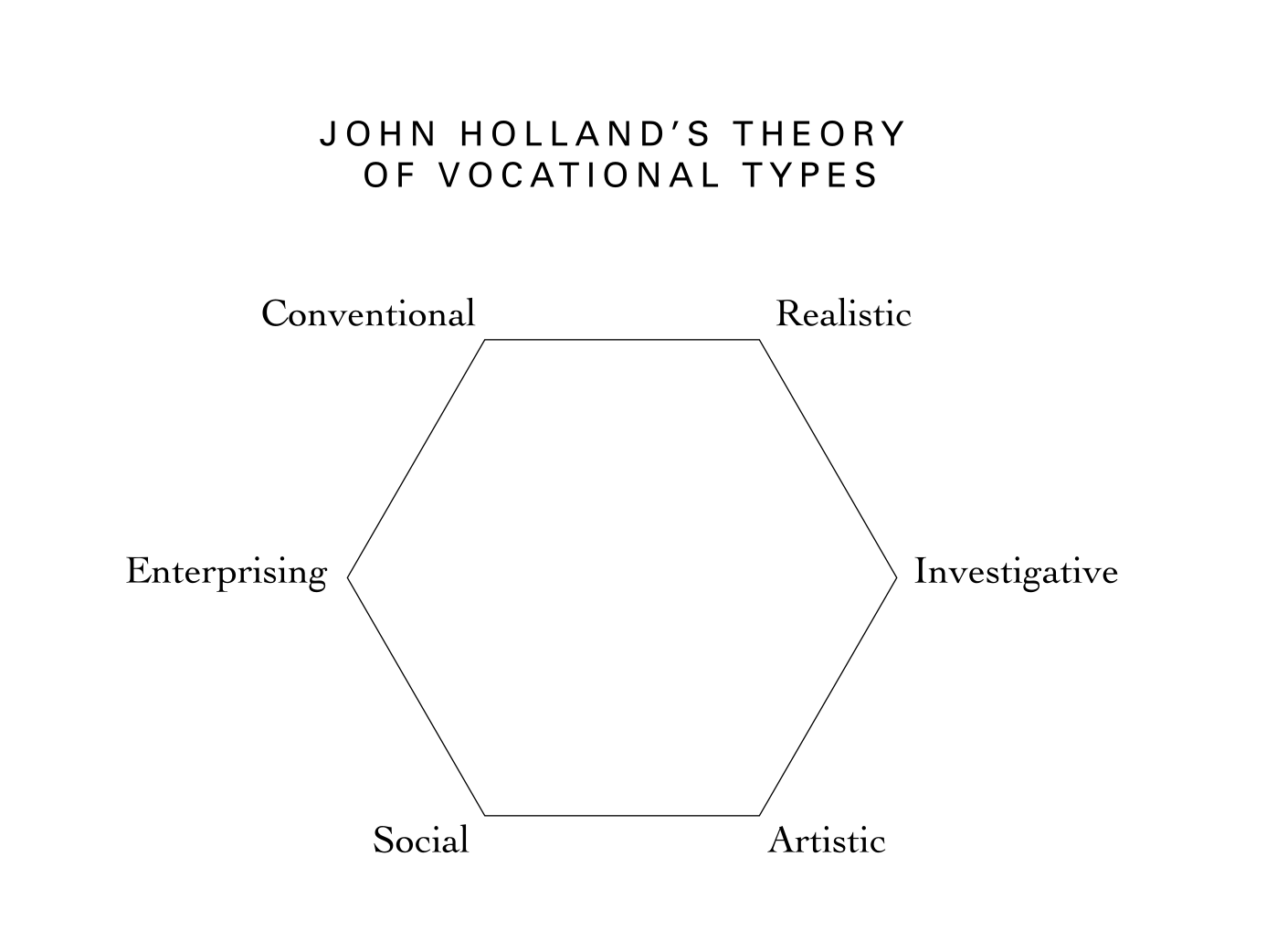

John Holland’s (1997) theory of vocational types has been the dominant version of the matching model over the past 50 years. While Holland quietly insists his is a more general theory of personality, 95% of the research on his model (and there have been over a thousand published studies of his theory) relates to the impact of matching people’s interests to their work environments. It is popular because it makes so much common sense — and because it works.

Holland holds that the world of work can be thought of as being (and indeed has been measured to be) composed of six basic types of work environments, almost like work cultures, those being Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional. Lucky for us, people also come in those same six flavors. The principal task is to assess your Holland type and then shoot for an occupational environment that more closely fits your type. If you succeed, life is good. If you are mismatched, life is not so good, at least in terms of job satisfaction, productivity, job tenure, etc.

Some types are more alike than others, a finding that has been repeated across cultures around the world, and those relationships approximate the hexagon shown. Even a close match (to a type on either side of yours) is better than a poor match (finding yourself in an environment clear across the hexagon from your type).

While this model has great intuitive appeal, and it has been our best effort for predicting job satisfaction, it still only accounts for 10-15% of the variability in that outcome. I believe we have pursued it because it does help some people make choices, it does explain some of the differences in the world of work, and it does make us look more scientific.

But there have been countless clients who have come to us for help who have had relatively flat interest profiles, meaning they looked as much like one group as any other. But instead of telling them that interests aren’t going to work for them, we tried to squeeze a tiny bit of truth out of an interest inventory that really had none to offer — in part that is because we didn’t know what else to do, or because we were trained with no other tools, or because the client had already shelled out ten bucks for the test and we didn’t know how to tell them, no, sorry, but you don’t get to use interests.

Beyond interests, personality adds only a little to helping us find “the match,” and the need to measure abilities rarely comes into play, particularly with college students. If someone is capable of succeeding as a student at KU, it is typically not a lack of ability that will make or break them in any given major, but instead their level of effort and luck. Mount Oread is covered with the memories of marginal students who have gone on to greatness, and with the ghosts of geniuses who lasted only one or two semesters.

Summary of Argument 1. Matching a person’s interests to an ideal occupation or field only predicts a small amount of their likely success or satisfaction.

Know thyself (Temple to Apollo at Delphi). To know thyself is the fundamental requisite (Parsons). Only the shallow know themselves (O. Wilde).

Argument 2: We aren’t very good at identifying why we like the things we like.

Now you’re saying to yourself, “That’s not me, I know exactly what I like.” Well, good for you. If you are good at it, then this is a non-issue for you. But the clients we serve often get stuck because it is not immediately obvious to them what will make them happy. And for those folks, trying to make that list of things that I like can get them in a heap of trouble.

Vocational psychology has relied most heavily on a model of vocational introspection and choice that is largely conscious and willful. There is a growing body of literature, however, that challenges this picture, and concludes that most of the processes involved in choosing are unconscious. The ability of the conscious mind to attend to and evaluate alternatives is severely limited, while the amount of information processed unconsciously is vast, and these unconscious processes set in motion choices and behavior based on that processing.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for that position was summarized in the April 1999 American Psychologist, devoted entirely to the issue of the role of will in behavior and choice. Denise Park (1999), serving as action editor of that issue, summarized the findings this way: “There are mental activations of which we are unaware and environmental cues to which we are not consciously attending that have a profound effect on our behavior and that help explain the complex puzzle of human motivation and actions that are seemingly inexplicable, even to the individual performing the actions.”

Conscious thought is very expensive. Norretranders (1998) claims that only one millionth of our sensory input is processed consciously, with the rest going on automatically or outside conscious awareness. Such automatic processes are helpful in that they act as “mental butlers,” aware of our preferences, and taking care of activities without our having to think consciously about them. Pinker (1997) concludes that 98% of incoming information is processed unconsciously, and uses the analogy of a spotlight on a stage to signify how we are able to shift our conscious awareness, but at any given moment are only able to focus on a small portion of all that is currently being processed.

When we use conscious processing to make choices, we utilize mental energy that is thus immediately unavailable for other (sometimes critical) tasks. A recent study (Recarte & Nunes, 2000) showed that when drivers are given a mental puzzle to solve, they make fewer glances at the rearview mirror and at the console. Epstein (1994) offered a view of such processing that includes what he terms the cognitive unconscious. This is not the unconscious of psychodynamic theory; rather, a storehouse of learning connections that allows many of the tasks involved in day-to-day existence to happen outside of the conscious stream of awareness.

When a new task is first attempted, like driving a car, every little behavior is noticed, right down to how far to turn the steering wheel to keep the car between the lines. Once the behavior is thoroughly learned, however, responsibility for that behavior is relegated to the unconscious, leaving the conscious processor available for other work. Attention is still necessary, and steeringwheel- turning can be brought back to conscious awareness; but if a normally recognized goal is approached in a normally recognized fashion, most of the work to get there is accomplished at this unconscious level. It is important to note that, while these authors argue for automatic decision-making, they also acknowledge that such automatic processes usually yield results consistent with what has in the past brought us satisfaction.

Now for a critical point. Several writers (Bargh, 1990; Bargh & Barndollar, 1996; Nisbett & Wilson; 1977) argue persuasively that when deciders do attempt to retrace the steps used in making a particular decision, they often make grievous errors. Nisbett and Wilson titled their article, “Telling more than we can know,” and citing studies on learning without awareness, subliminal perception, order effects, and the effects of others’ presence on helping behavior, built a case for consistent errors in the reporting of decisional considerations. This has led to the observation that people don’t think; they only think they think.

Worse still, there is evidence (Henry, Moffitt, Caspi, Langley, & Silva, 1994; Wilson, Lisle, Schooler, Hodges, Klaaren, & LaFleur; 1993) that reflective introspection can, under many circumstances, lead people away from the outcomes that persuaded them to introspect in the first place. Bargh and Barndollar (1996) described a “wise unconscious,” a repository of chronic goals and motives. Its wisdom comes in that decisions made and implemented at the unconscious level are often more satisfying than decisions made when the conscious processor steps in. When forced to reflect about reasons, the decision-maker actually is being forced to generate material not readily available. It is at this point that decision makers engage in many of the heuristics identified by Tversky and Khaneman (1974) and generate reasons not all that salient to the decision at hand (but readily available to memory or similar to a significant exemplar). This is the same Khaneman who yesterday we learned won the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics with Vernon Smith, a 1951 masters degree graduate of KU.

Human decision-making can best be thought of as mess management. Ackoff (1974).

People are unaware that they engage in the above errors of information processing. And worse still, they are convinced that they do not. When they are asked, for example, to list those values that are most important to them, most salient in their decisionmaking process, they will almost certainly (with lesser or greater amounts of effort) generate such a list. Research has demonstrated that such lists often have little in common with the actual criteria driving their choices (Slovic, Fleissner, & Bauman, 1972). Cochran (1983) and Krieshok, Arnold, Kuperman, and Schmitz (1986) reported that high school and college students were unable to accurately articulate the constructs they used in making judgments about the attractiveness of various occupational alternatives.

Unfortunately, the generation of such a list is at the foundation of virtually all the computerized guidance systems, and is integral to the way most career counselors practice with their clients when they say to them in one way or another, “Let’s figure out what’s important to you in a career, and then generate a list of alternatives that meet those criteria.”

From a constructivist or narrative point of view, what is in question here is how we come to tell the stories we tell about who we are. How do we come to tell folks we are interested in working with people, good at math, shy, or outgoing? Our own experience of the world yields an easy answer to that question. We reflect on it, and we come to conscious conclusions to those kinds of questions. But the literature says the real story is buried somewhere beneath the conscious surface, and that we are susceptible to the problem of focusing on one unrepresentative spot on the stage, rather than discerning the whole stage and what’s really going on.

Gregory, Lichtenstein, and Slovic (1993) recognized the delicate role played by someone helping another delineate their values, and it is a role very similar to the one played by career counselors. They described such facilitators “not as archaeologists, carefully uncovering what is there, but as architects, working to build a defensible expression of value” (p. 179). This is the closest to postmodernism as I get. I used to believe that each of us carried within us a critical set of skills, values, and personality traits that if articulated just right would make clear “the match.” My role as a career counselor was to go in and find that data, uncover it like the archaeologist, and bring it out. Now I know that as soon as a client begins to think about such things, they are not finding the story, they are in a very real sense constructing the story, and I am inevitably helping them construct it.

The Kid in the Back Seat. When I was a youngster my parents always owned a big station wagon. The rear seat of the station wagon, what we called the “way-back” inevitably faced rearward, allowing the occupants a most unusual experience of any trip. Unlike riders in the front or middle seats, the kid in the back seat always sees the world after things have happened, never before. If you were to ask the kid in the backseat where she went on vacation, she could tell you various sites she remembers (the Statue of Liberty, the Grand Canyon) and you could piece together a reasonably good approximation of the itinerary. But you’d always have to keep in mind that the kid in the back seat was pretty much guessing about the actual intentionality of the driver. You could presume that there was an adult in the driver’s seat, someone who was responsible and generally made good decisions about routes. You might even imagine another grownup in the passenger’s seat, reading maps and making suggestions. But if you limited your interview to the kid in the back seat, you would be presuming a great deal, and probably missing a lot.

I think the literature on decision-making says consciousness is the kid in the back seat. Our unconscious is driving, and for the most part is making good decisions, but so far we have not found ways to communicate directly with the driver. Now, like only the youngest of way-back riders, our consciousness still thinks it is controlling the car, actually making the choices about where to go and how to behave. I think the literature suggests otherwise. The issue of the American Psychologist that I mentioned earlier concludes fairly strongly that, while we experience the world as conscious choosers, we either are not that way at all, or at least enjoy much less conscious authority over decisions than we believe.

Many of those researchers hold a position I described in a 1998 article as Anti-Introspectivist (Krieshok, 1998). When I wrote that review, I was shocked and even disturbed by what I had found in the literature, and I was afraid that readers might associate my name with that point of view, while I was just trying to describe what I had found. Since then I have become more and more convinced of their position, and now I probably should be associated with that label.

Summary of Argument 2. There is whole lot more going on under the hood than we give credit to. Many, if not most, of our decisions are a product of processes that are outside of conscious awareness — not because we are repressing them or hiding from them, just because that’s the way human mental systems operate most efficiently. In the course of day-to-day choices this is not a problem. It’s only a problem when we cannot easily make a choice (as with an undecided major). And the really complicated piece is that when we try to access those processes we cannot, but we think we can, yielding data that is not very reliable with which we try to “think through” pesky decisions.

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that ain’t so that gets you into trouble. — Mark Twain

Argument 3: Even if there was a time when matching did work, today’s world of work is so turbulent that we can no longer count on keeping our match.

The world of work that my father entered right out of the service in 1945 was quite different from the world of work I moved into out of college in 1974, but radically different from the world of work my children are moving into today. With little more than a high school diploma my dad was able to get a high-paying job as a steel worker, a job he held for 35 years before he retired at the age of 60. Well-paying jobs requiring low skills or skills acquired on the job were common for workers in my father’s generation, and most of my uncles back in Granite City, Illinois, worked in the mills, raised families, and lived what for most Americans was the good life. As H. B. Gelatt said, “Growing up ain’t what it used to be.”

Two factors have intervened in the past half century that have reshaped the American world of work, and not always for the better for the average worker. Those two factors are globalization and increased technology. Combined, those factors have contributed greatly to the disappearance of jobs that paid well but required little first-day-on-the-job skills. Many mill jobs were moved to countries whose standard of living allowed companies to pay considerably less for work that did not require higher levels of education, yielding a widening gap in the U.S. world of work between highskilled, high-paid workers and low-skilled, low-paid workers. That trajectory continues today and into the foreseeable future.

In addition, a work environment marked by apparent loyalty on the part of the company toward its workers (if it ever existed) has given way to a work environment marked by mergers, downsizing, plant closings, and startup companies with high failure rates. In order to stay competitive, companies strive to develop a workforce that is nimble, or capable of shifting from one project to an unrelated project at the drop of a hat. Companies hire fewer permanent employees and more temporary employees who receive fewer benefits and less stable working conditions. Add to that the continuous rate of change due to technological discoveries and those of us who hold our jobs long enough to go up for tenure should count our blessings.

I am worried about what the world of work holds for the next generation. I am coming to believe that no matter what line of work they might choose, no matter how talented they are, no matter how clever they are in their career choices, that they may have little control over the course of their work lives. And that scares me for them.

To be a successful worker in the new economy requires a broader set of skills, the starting point of course being basic skills: reading, writing, and computation; plus “hard” (technical) and “soft” (interpersonal and communication) skills; and, most importantly, the ability to learn continuously throughout life.

Successful workers of the future will be able to learn quickly and adapt, and they must be able to work as team members. In addition, global workers need flexibility, problem solving and decision-making ability, adaptability, creative thinking, selfmotivation, and the capacity for reflection, and finally, complementarity — the ability to facilitate the work of others. Lots of un-American team notions.

According to Bailyn (1992), “the traditional system is geared to matching an individual to a job that has been carefully defined independently of the person filling it” (p.381). In the new economy, jobs may be shaped more by the qualities of those performing them, and status and compensation may be attached to people, not positions. Career educators need to help people become individual career negotiators acting as agents in their own behalf, and to rethink work and career to identify how they can contribute to an organization according to their abilities and personal circumstances.

Summary of Argument 3. Due in part to globalization and technology, the world of work is less stable, less loyal, and less predictable, making it essential that workers take responsibility for their own relationship to the world of work.

The Adaptive Vocational Personality Style

My three arguments lead me to the conclusion that vocational psychology needs to redefine its agenda for helping workers negotiate their relationship to work. Instead of placing so much emphasis on identifying a one-time match for every citizen, we should loudly proclaim that we are now in the business of helping citizens develop their adaptive vocational personality style. So what in the world would that look like?

Many vocational psychologists have already begun developing this agenda. Back in 1975, Frederickson, Rowley, and McKay argued that since humans are capable of flexibly responding to a wide variety of environments, counselors’ efforts should be directed at helping clients learn flexibility and elasticity in coping with change. Gelatt (1989) coined the term “positive uncertainty” which exhorted us to be focused and flexible about what we want, aware and wary about what we know, objective and optimistic about what we believe, and practical and magical about what we do. Gelatt’s work is important because it evolved over a span of several decades from a traditional rational model of decision-making to this newer (some would say) post-modern model of living through decisions. Gelatt once wrote, “It used to be the future was uncertain. Now the past and present are uncertain as well.”

Donald Super (who along with John Holland is seen by most everyone as one of the two dominant vocational theorists of the last century) developed the construct of adaptability to describe the desirable state that all of us should have in our relationship to work (Super & Knasel, 1981). One of my students, Chris Ebberwein (2000), completed his dissertation a couple years ago using Super’s model to look at the experience of workers who had been laid off from their jobs in Kansas City. Except in the rare cases of workers who had spouses with significant income or workers with exceptional severance packages, those who fared best were workers who while they were still working in jobs they saw as stable had begun or continued to prepare themselves for the eventuality that their current job might go away. They did this in a variety of ways, including going on to school for more training, setting aside a nest egg, or developing their network of contacts so they would always have a Plan B on the drawing board.

Perhaps the most important work in this area is that of John Krumboltz, Kathleen Mitchell, and Al Levin. They have written about something they call “planned happenstance” which, like the name implies, combines a traditional planful stance with an appreciation for the happenstance that inevitably occurs in each of our lives. Only recently have vocational theorists gotten comfortable including fate in our theories of vocational choice.

In large part that is in response to research that shows a very high percentage of workers believe their own relationship to work has been significantly impacted by one or several life-course-changing events or encounters (Mitchell, Levin, & Krumboltz, 1999).

If, in fact, this happenstance marks most adult lives, how might we exploit it in a positive way? How might we learn to embrace (rather than fear or avoid) situations that might lead to chance encounters or unpredictable outcomes? Can we learn even to create such pregnant situations, to place ourselves in fate’s way, and make it more likely we will be in the right place at the right time? And can we learn to recognize those situations and events when we are in their midst? These are not the kinds of skills we have traditionally promoted. Most of our models of career decisionmaking would encourage us to strive to eliminate outcomes outside the boundaries of our plan.

The five pillars of Planned Happenstance include curiosity, flexibility, persistence, optimism, and risk-taking. These are the skills and characteristics, when applied to one’s relationship to the world of work, that will allow us to be the adaptive person Super and Knasel (1981) described and that Ebberwein identified in laid-off workers. These are the elements I would strive to develop in students at every level, from early elementary grades through graduate school, and in workers at every age.

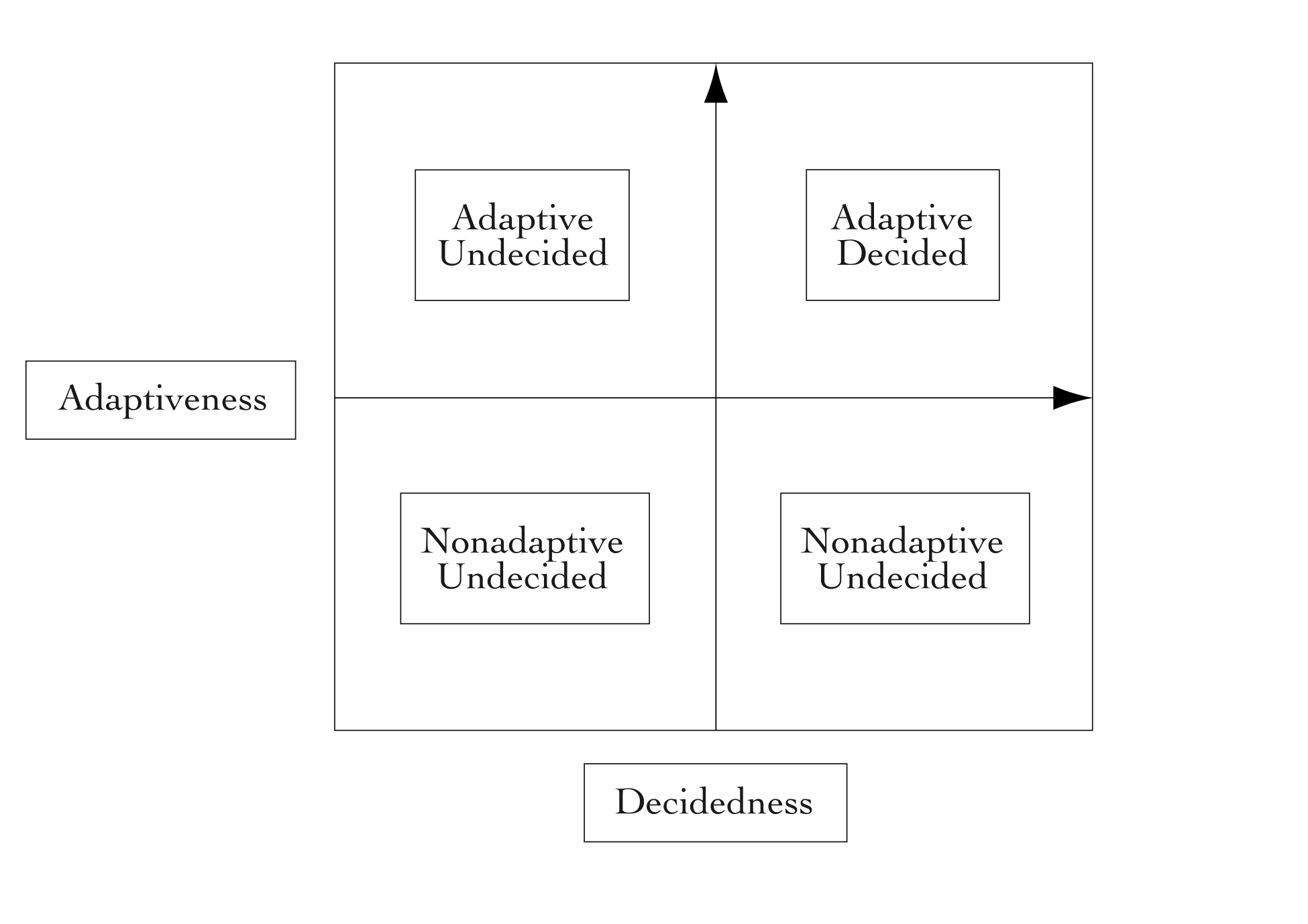

If we consider a 2x2 matrix of college students who can be adaptive-nonadaptive and decided-undecided, I would predict more positive outcomes for the adaptive group over the decided group. Of course the decided adaptive quadrant would be expected to do best, and the undecided nonadaptive the worst. But I would place my money on the adaptive undecided over the nonadaptive decided, even though most vocational theories and most colleges would worry more about the undecided student. As long as the adaptive undecided gets out there and mixes it up with the world of work, they will eventually find a major that will allow them to learn what they need to learn, and they will eventually find a niche in the world of work, or should I say a next niche in the world of work.

What scares me more is the person who comes to college, who lands on a major with little effort, but then has the attitude, “Whew, I managed to dodge that bullet,” and then stays in their room studying in their major for the next few years. I worry that they are missing out on the opportunity to develop their skills at interacting with the world, which soon translates into the world of work.

Conclusions and Recommendations

1. Put less emphasis on decidedness as an outcome.

As I have studied this literature over the past several years, I have grown in my respect for what must be going on under the surface. I was once a zealot fighting to eradicate undecidedness from the face of the earth. Now I recognize many good reasons for undecidedness, including family issues, lack of exposure to environments because of age, racism, or sexism, and the inevitable lateness of development of more sophisticated interests and skills. Instead of simply flooding the individual with more information about themselves and the millions of possible work alternatives, now I more respectfully honor the delicate process of identity development.

2. Most people make good decisions when left on their own.

Don’t try to force a commitment to something prematurely. Perhaps your particular blend of skills and interests won’t really come together and make themselves obvious until you have been in the world of work for a number of years, are well into college, or even in graduate school.

3. When it comes to the matching part, rely less on testing and more on experience.

If deciders cannot know exactly what information is most important to them, exposing them to the richest data set available will likely expose them to the information they need, even if they can’t say what it is. In other words, it may not be obvious whether it’s prestige, a sense of being where the action is, or helping people that is most important, but if given the opportunity to shadow or volunteer or work part-time for a prosecuting attorney, a nurse, and an engineer, experiencing each of those variables firsthand in each of those experiences will make the data available when it comes time to decide. This would argue very strongly for interventions such as shadowing, informational interviewing, and even multimedia presentations of occupational information. Wanous (1973) discovered that a Realistic Job Preview that offers job applicants a fuller picture of the job for which they are applying leads to employees who are more satisfied and who stay in the position longer.

4. Those who are most desperate for decidedness are usually those who can least afford it.

Said another way, it is important to clearly differentiate between decidedness and commitment. While we can honor the delicate process of identity development, we often must also put bread on the table or enroll in next semester’s classes. While I will often need to commit to a particular course of action in order to be in the real world, I cannot make the mistake of seeing that commitment as my choice of a life’s work. In fact, I might argue that trying to choose a life’s work at all causes more trouble than it’s worth. Perhaps a better stance to take is that I am looking for opportunities to work at something that is meaningful for me now, realizing that things (or I) could change and require me to pull up stakes and look for different work or different circumstances.

5. Promote an appreciation for planned happenstance and positive uncertainty.

Learn how to play a more active role in “creating” chance events. The theory of planned happenstance holds that in the end, getting a job is always a matter of being in the right place at the right time. All our planning can do is make it more likely we can be in A right placed at the right time. Develop an attitude of asking questions, hanging out in places where interesting things are happening, getting experience in environments that are of interest to you, and meeting people who are doing things that interest you.

6. Prepare folks to be adaptive agents.

Remember Jerry McGuire and the way he managed his superstar football player. Almost none of us gets that kind of agent, but we all need someone who knows our areas of genius, who knows what opportunities are out there in the world of work for our genius, and works to get us ready to go out there and chase some of those down. In today’s world of work, no one else will play that role, so we need to do that for ourselves. Even in relatively stable work environments, I suspect adults are healthier if they resist seeing themselves and their relationship to work as finished products. What I want for my own children is an attitude of excitement and discovery about the world of work. What I don’t want is an attitude that once they get this figured out they can get on with other life tasks and put this one to rest.

7. Career counseling is very complex work.

When clients come to us, they usually believe that we will be able to help them make some of the most difficult decisions in their lives in a single session. Too often, we agree with them. Between our self-help materials, our peer counseling models, and our webbased never-see-a-counselor interventions, we have contributed to a sense that life/career development is no big deal. I think the literature on how the mind works demonstrates how complex career choice must be, and how easily the human mind can get lost in a veritable sea of information. Very often, however, clients don’t really care where the decision comes from, and don’t really want to have to look at occupational information, but instead are more focused on getting the decision making process over with and getting on with its implementation. Renegotiating the career counseling contract with a client who is expecting big outcomes in exchange for little time and effort requires some of the most sophisticated counseling skills we possess.

8. The postmodern-ness of career counseling.

Recall Gregory, Lichtenstein and Slovic (1993) who say we are not like archaeologists trying to “uncover” what is laying there under some dust or debris, but more like “architects” trying to help the person construct a meaningful story. That is very different from how I have typically approached my work. I have wanted to believe I could do assessments or have clients tell me stories in response to well-chosen questions, and we could get “it” out. We might argue about the best way to arrange what we got out, should we attend to interests, values, personality, or skills, but I believed that what we were getting out was in fact already inside. I now believe that asking the question prompts the creation of a plausible vision of what “must be in there,” “what should be in there,” or “what I wish were in there.” How easy is it to manipulate the stories I tell myself of who I am or what my interests are? For example, in a laboratory setting, could my sense of the appropriateness of various gendertraditional occupations be influenced by the presence of a confederate peer who makes casual remarks about others’ choice of major before or during an experiment? And if so, how long might such an effect last?

9. This may be less of an issue in other cultures.

I would certainly expect that this phenomenon could look differently in non-Western cultures. Those economies that are less insulated from world markets or that exist in cultures that are less competitive and every-person-for-the-self might assume more responsibility for the welfare of workers. At the same time, U.S. workers from such cultures may be most at risk for difficulties in dealing with this situation in the U.S. world of work.

10. Can we teach career adaptability?

Is career adaptability like a personality trait that is difficult to change, or more like a set of learned behaviors amenable to intervention? I envision something of a “boot camp” for students from elementary school to college, at which we train them to embrace positive uncertainty and planned happenstance. I don’t see very much of an appreciation for these attitudes right now in the general population, perhaps we are still stuck in the era of trusting that the world of work will somehow take care of us, if only we insert ourselves into it in the most congruent fashion.

11. What are the normal human limits to adaptability?

The world of work is very different now from the world of work of 30 years ago. It lacks predictability — a commodity that humans need desperately for survival. A big question for me is whether or not we can teach people to not decide, to live with the discomfort of not rushing to judgment. I’m just not sure how much of this we as humans can tolerate, even though it fits with what reality calls for.

Final Conclusion

I am a humanist and, while I was at first troubled by the research on decision-making, I am swayed by the weight of it. My vision of humankind is bigger than it used to be. I now see folks as struggling, but on many different fronts. I now believe I am bombarded by billions of bits of information daily, and while my unconscious mind is working night and day to make sense of it, it only lets my conscious mind in on a part of it, and that’s probably a good thing.

I am fascinated by how this must be happening, but I now see it as enormously more complex and incredible than I did five years ago. We are so complex, and we are not simply predictable. We are in some ways easily influenced by the words of others, family, television, and peers. We may easily move away from that which might most wholly satisfy us because of what others say. And getting at that which would be most satisfying may be terribly difficult, and may take a lifetime, and we may never, most of us, ever get a peek at it.

I gravitate to the notions of planned happenstance and positive uncertainty. I want students to get out and explore with a sensible fearlessness, to always take a ready stance, to take on a “scrappy” attitude in how they interact with the world of work. I want them most of all to not be afraid of assuming that stance and that attitude, and my concern is that the way we approach things now may work against that attitude of scrappiness and open mindedness.

I want to take students out for field trips. I want to expose them to new and rich environments; I want to tell them, over and over, that they don’t need to tell me what they want to be when they grow up. I want to tell them that, in spite of what their friends and colleges to which they are applying try to tell them, they don’t need to know with any certainty what they want to do. Indeed, it would be so much better for them to tell me, colleges, but especially themselves, that they do not know, so they are exploring.

References

Bailyn, L. (1992). Changing the conditions of work. In Career development: Theory and practice, edited by D. Montross and C. Shinkman. Springtield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Bargh, J. A. & Barndollar, K. (1996). The unconscious as repository of chronic goals and motives. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A.

Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action. New York: Guilford Press.

Bargh, J. A. (1990). Auto-motives: Preconscious determinants of thought and behavior. In E. T. Higgins & R. M. Sorrentino (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition (Vol. 2, pp. 93-130). New York: Guilford.

Cochran, L. (1983). Implicit versus explicit importance of career values in making a career decision. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30, 188-193.

Ebberwein, C. A. (2000). Adaptability and the characteristics necessary for managing adult career transition: A qualitative investigation. Dissertation. University of Kansas.

Epstein, S. (1994). Integration of the cognitive and the psychodynamic unconscious. American Psychologist, 49, 709-724.

Fredrickson, R. H., Rowley, & McKay. (1974). Multipotential-A concept for career decision making. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the American Personnel and Guidance Association (New Orleans, Louisiana, April 1974). (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 092 827)

Gellatt, H. B. (1989). Positive uncertainty: A new decision-making framework for counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36, 252-256.

Gregory, R., Lichtenstein, S., & Slovic, P. (1993). Valuing environmental resources: A constructive approach. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 7, 177-197.

Henry, B., Moftitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Langley, J., & Silva, P. A. (1994). On the "remembrance of things past": A longitudinal evaluation of the retrospective method. Psychological Assessment, 6, 92-101.

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments. Lutz, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Krieshok, T. S. (1998). An anti-introspectivist view of career decision making. Career Development Quarterly, 46, 210-229.

Krieshok, T.S., Arnold, J. J., Kuperman, B. D., Schmitz, N. K. (1986). Articulation of career values: Comparison of three measures. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33, 475-478.

Mitchell, K., Levin, A., & Krumboltz, J. (1999). Planned happenstance: Constructing unexpected career opportunities. Journal of Counseling and Development, 77, 115-124.

Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84, 231-259.

Norretranders, T. (1998). The user illusion. New York: Viking.

Park, D. C. (1999). Acts of will. American Psychologist, 54, 461.

Parsons, F. (1909). Choosing a vocation. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Pinker, S. (1997). How the mind works. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Recarte, M. A. & Nunes, L. M. (2000). Ettects of verbal and spatial-imagery tasks on eye fixations while driving. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 6, 31-43.

Richardson, M. (1993). Work in people's lives: a location for counseling psychologists. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 40, 425-433.

Slovic, P., Fleissner, D., & Bauman, W. S. (1972). Analyzing the use of information in investment decision making. Journal of Business, 45, 283-290.

Super, D. E., & Knasel, E. G. (1981). Career development in adulthood: Some theoretical problems and a possible solution. British Journal of Guidance c Counselling, 9, 194-201.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 184, 1124-1131.

Wanous, J. P. (1973). Ettects of a realistic job preview on job acceptance, job attitudes, and job survival. Journal of Applied Psychology, 58, 327 332.

Wilson, T. D. & Schooler, J. W. (1991). Thinking too much: Introspection can reduce the quality of preferences and deci- sions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 181-192.

Wilson, T. D., Lisle, D. J., Schooler, J. W., Hodges, S. D., Klaaren, K. J., & LaFleur, S. J. (1993). Introspecting about Ωeasons can reduce post-choice satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19, 331-339.